Missouri researchers have found a pattern of gene expression associated with aggressive tumors that could produce a diagnostic test that could alter the clinical management of oral cancer patients.

Researchers at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis discovered a way to predict the aggressiveness of similar tumors in humans by studying mouth cancer in mice, an early step toward a diagnostic test that could guide treatment. Their work was outlined in a recent issue of Clinical Cancer Research (June 1, 2014, Vol. 20:11, pp. 2873-2884).

"All patients with advanced head and neck cancer get similar treatments," stated Ravindra Uppaluri, MD, PhD, an associate professor of otolaryngology, in a press release. "We have patients who do well on standard combinations of surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy, and patients who don't do so well. We're interested in finding out why."

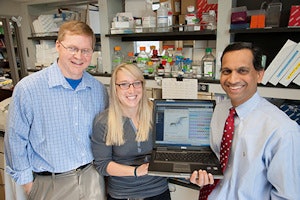

Ravindra Uppaluri, MD, PhD (right), led a team that developed a preliminary diagnostic test that identifies aggressive oral tumors. Michael D. Onken, PhD (left), and Ashley E. Winkler are co-authors of the paper. Image courtesy of Washington University School of Medicine.

Ravindra Uppaluri, MD, PhD (right), led a team that developed a preliminary diagnostic test that identifies aggressive oral tumors. Michael D. Onken, PhD (left), and Ashley E. Winkler are co-authors of the paper. Image courtesy of Washington University School of Medicine.The investigators found a consistent pattern of gene expression associated with tumor spreading in mice. Analyzing genetic data from human oral cancer samples, they also found this gene signature in patients with aggressive metastatic tumors.

"We didn't automatically assume this mouse model would be relevant to human oral cancer," noted Dr. Uppaluri, who performs head and neck surgeries at Barnes-Jewish Hospital in St. Louis. "But it turns out to be highly reflective of the disease in people."

Humans develop oral cancer through the repeated application of carcinogens, so the research team followed the same strategy with the mice, rather than developing the cancers genetically.

"Patients often have a history of tobacco and alcohol use, which drive the development of these tumors," Dr. Uppaluri explained. "We felt that exposing the mice to a carcinogen would be more likely to produce similar kinds of tumors."

Sometimes, the researchers found, this exposure produced tumors in the mice that did not spread but other times resulted in aggressive metastatic tumors, similar to the variety of tumors seen in humans.

Dr. Uppaluri's team then collaborated with Elaine Mardis, PhD, the co-director of the Genome Institute at Washington University, to find out whether the mouse and human tumors also were genetically similar. They compared their mouse sequences to human datasets from the Cancer Genome Atlas.

"When we sequenced these tumors, we found that a lot of the genetic mutations present in the mouse tumors also were found in human head and neck cancers," Dr. Uppaluri stated.

A common signature in the expression of about 120 genes that was associated with the more aggressive tumors, whether in mice or people, was identified by the researchers. They confirmed this signature using data collected from 324 human patients. Then, using oral cancer samples from patients treated at Washington University, researchers developed a proof-of-concept test from their signature that identified the aggressive tumors with about 93% accuracy.

Dr. Uppaluri now has a patent pending on this technology and recently received funding from the Cancer Frontier Fund to develop a laboratory test that predicts aggressive disease.

"These kinds of tests are available for other types of cancer, most notably breast cancer," Dr. Uppaluri stated. "They are transformative genetic tests that can alter the clinical management of patients, tailoring therapies especially for them. It's our goal to develop something like that for head and neck cancer."

The research was supported by the National Cancer Institute, the National Human Genome Research Institute, and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, which are part of the National Institutes of Health.