Daily brushing and flossing not only lead to healthy gums and bright, shiny teeth, but they can protect one's heart, according to research published in the International Journal of Oral Science.

Researchers led by Yuka Shiheido-Watanabe from Tokyo Medical and Dental University reported that a common oral pathogen can stop cardiac myocytes from repairing themselves after a heart attack caused by coronary heart disease.

Heart attacks occur when blood flow in the coronary arteries is blocked. This results in an inadequate supply of nutrients and oxygen to the heart muscle, and, ultimately, the death of cardiac myocytes. Cardiac myocytes use a process known as autophagy to dispose of damaged cellular components, which prevents the myocytes from causing cardiac dysfunction.

The periodontal pathogen Porphyromonas gingivalis can be found at the site of occlusion in myocardial infarction, which can heighten post-infarction myocardial fragility, according to previous research. However, the researchers noted that the underlying mechanisms for this effect are unknown.

Shiheido-Watanabe and colleagues for their study developed their own version of P. gingivalis that does not express gingipain, which can prevent cells from undergoing programmed cell death in response to injury. They then used this bacterium to infect cardiac myocytes in mice.

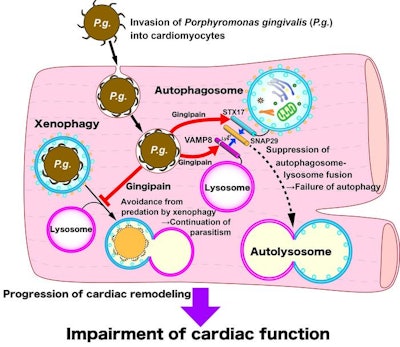

Gingipain released by P. gingivalis cleaves VAMP8, thereby inhibiting autophagy through preventing autophagosomes-lysosome fusion, which causes cardiac dysfunction. Image and caption courtesy of the department of cardiovascular medicine at Tokyo Medical Dental University.

Gingipain released by P. gingivalis cleaves VAMP8, thereby inhibiting autophagy through preventing autophagosomes-lysosome fusion, which causes cardiac dysfunction. Image and caption courtesy of the department of cardiovascular medicine at Tokyo Medical Dental University.

The researchers found that the viability of cells infected with the mutant bacterium lacking gingipain was significantly higher than that of cells infected with the wild-type bacterium. They also found that the effects of myocardial infarction were more severe in mice infected with wild-type P. gingivalis than in those infected with the mutant pathogen lacking gingipain.

The team also reported that that gingipain interferes with the fusion of two cell components known as autophagosomes and lysosomes, a process that is crucial to autophagy. In the mouse models, this led to an increase in the size of cardiac myocytes and accumulation of proteins that would normally be cleared out of the cells to protect the cardiac muscle. The study authors suggested that based on their results, treating this common oral infection could help reduce the risk of fatal heart attack.