DrBicuspid.com is pleased to present the latest installment of Leaders in Dentistry, a series of interviews with researchers, practitioners, and opinion leaders who are influencing the practice of dentistry.

We spoke with Joel M. Weaver, DDS, PhD, a dentist anesthesiologist who has practiced in the Ohio State University dental clinic and hospital operating rooms for more than 30 years. Partially retired since 2007, Dr. Weaver is the immediate past president of the American Society of Dentist Anesthesiologists and past president of the American Dental Board of Anesthesiology and the American Dental Society of Anesthesiology. He is currently the editor-in-chief of Anesthesia Progress and national anesthesia spokesperson for the ADA.

Dr. Weaver shared his thoughts on a number of issues in dental anesthesiology, including drug shortages, the safety of administering general anesthesia to very young patients, and who should be allowed to administer general anesthesia.

DrBicuspid: What are your thoughts on the safety of general anesthesia for very young patients?

Joel M. Weaver, DDS, PhD.

Joel M. Weaver, DDS, PhD.

Dr. Weaver: There is certainly conflicting data. It's all very preliminary; it initially started out with rodent studies, and now they've looked at nonhuman primates. These studies are looking at the very young as opposed to what would be the equivalent of 4- to 5-year-old children, who would be likely to have general anesthesia for dentistry. Some of those studies are giving mice exposure up to 24 hours, which would be exceedingly clinically rare for a child. We're a long way away from filling in all the pieces of the puzzle to see if, in fact, there's anything to what scientists have observed under experimental conditions in nonhumans.

One thing that has to be made clear is that rarely is it entirely optional for young children to have anesthesia of any type. Even for younger children with massive caries at 18 months who can't eat, to not give them anesthesia could be inhumane and not safe. The dentist's drill runs around 400,000 rpms; if a little child brings his hand up to his mouth because he's uncooperative or precooperative, the drill could slice his hand like butter. So if the child is in pain and needs dental care, general anesthesia may be the only safe way to prevent psychological and physical harm.

Putting an uncooperative child in a headlock with no anesthesia to do dentistry on a semimoving target could impair his or her mental health. That's invading a body cavity by a stranger -- the dentist -- which could be devastating to the child without anesthesia and is perhaps the root of many dental phobias. Those patients might have benefitted from anesthesia.

When doctors are treating ear infections in very young patients, draining is always done under general anesthesia. It's a minimal procedure, yet insurance companies will typically cover it. The thinking is that it is medically necessary and general anesthesia is a part of the process.

Yet in dentistry the insurance companies don't always feel the same. "Why can't you just do it under local?" Perhaps it's the same child who had a 30-second procedure with ear tubes put in. And yet for hours' worth of dentistry, the child has to be placed in a headlock and the dentist tries to do the best he or she can. It's the way it seems to happen all too often, and it doesn't make sense.

Are insurers' efforts to limit payments affecting treatment plans?

That's a possibility. Dentists are pretty inventive; they do what they can with the skills they have. If insurance companies won't pay for dentist anesthesiologists to take their portable anesthesia equipment and monitors into the dentist's office to provide general anesthesia, or for dentists to take the patient to a surgicenter or hospital for anesthesia, then dentists have to do the best they can.

“For younger children with massive caries at 18 months who can't eat, to not give them anesthesia would be inhumane.”

— Joel Weaver, DDS, PhD

This problem is multifactorial. Parents have a responsibility to prevent caries, yet a lot of parents don't understand that giving a child a bottle of milk or sugary drink as a pacifier causes rampant decay. Every tooth in an 18-month-old may be decayed beyond saving. It not only happens in families of low income but also high income, when both parents work and a nanny without knowledge of a healthy diet leads to the same result.

Certain states make it very difficult for dentists to do sedation or administer anesthesia in their office. In California, a huge number of dentist anesthesiologists are able to travel from office to office to treat precooperative children who are 18 months old. Those laws are pro access to care. The practice is highly regulated, but the laws are still effective.

Other states, such as Florida, don't allow it. If the pediatric dentist happens to have the same training as a dentist anesthesiologist (which would be very rare), then the latter can come into the office to provide general anesthesia while the dentist does the dentistry. But if the pediatric dentist doesn't have that training, then the dentist anesthesiologist can't come into the office.

If I were a licensed Florida dentist with anesthesia training, I could administer general anesthesia and have an assistant monitor the patient while I did the dentistry as well. But I could not go to another office and just do the anesthesia while the other dentist does only dentistry like I could in California, Ohio, or other states where this type of practice is very common and very safe. Thus dentists in states with antiquated state dental board rules who can't use the service of a dentist anesthesiologist do the best they can to get these children out of dental pain.

Ohio has a good rules model. As a result of several bad outcomes many years ago, the dental board changed regulations to say that if a regular dentist is without any additional anesthesia training, they can use nitrous or minimal sedation for any patient, adult or child. But with injectable or swallowed sedative drugs, for children 12 and younger, the dentist has to have special training and a sedation permit from the board. Ohio has favorable laws for dentist anesthesiologists to come to those offices where the dentist doesn't have that training to provide advanced anesthesia services. It's a proactive state in that sense. But every state is different.

What are some of the endemic problems preventing a reliable supply of anesthetic drugs?

It takes a huge amount of money for companies to put drugs on the market, to go through the trials required by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Patent rights are held for a number of years while the companies try to recoup their investment; after the patent is no longer effective, the generic companies move in. One of the things that happens is if several companies are all trying to create a new version of an existing drug, one or two buy all competing companies. Then one goes out of business and there's only one supplier left, and often that company is offshore. Then if it has to shut down due to a disaster -- say in the Caribbean -- then manufacturing of that drug ceases.

Also, FDA inspections sometimes shut down factories for violations. All of a sudden, if there are no other manufacturers, then the drug is unavailable.

With propofol, there have been several misuses of that drug by physicians who are using it under unsanitary conditions, resulting in the spread of hepatitis B and C and perhaps other diseases as well. That should have nothing to do with the drug, yet lawyers go after the deep pockets, the drug company. The physician's malpractice insurance will only pay so much; when divided among 50 to 100 patients involved, there's not much money for any one individual, including the lawyer.

Who knows? Maybe they'll go after the trucking company and the tire company that supplied the tires on the truck that delivered the propofol! I'm being facetious, but you get the point. A huge, multimillion dollar judgment was levied against a company due to a dirty needle and the company threw in the towel. They no longer make propofol, and a shortage resulted.

Right now, dexamethasone -- an anti-inflammatory steroid -- is on restricted use at our hospital. We just got back a neuromuscular relaxing drug in the hospital that is a treatment for life-threatening anesthesia complications. It was restricted for several months. The problem has finally been resolved, but these types of shortages keep occurring. The list goes on and on.

There's a senate bill, SB 296, being considered right now that would allow the FDA to require manufacturers of critically necessary drugs to let the FDA know in advance that they're not going to make the drug anymore. Then the FDA can help companies in trouble who are going out of business. The FDA may give them advice or guidance on how to fix a manufacturing problem to resume production rather than shutting down. Similar legislation has been introduced in the House of Representatives by Rep. Diana DeGette (D-CO).

What sort of advancements do you see on the horizon related to dental anesthesia?

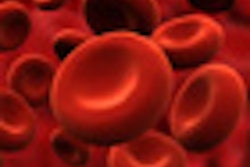

There are always advances in various types of drugs that can be important to anesthesia. For example, there is a new drug called Pradaxa that, for some indications, will replace a very bothersome drug: warfarin.

Warfarin is an anticoagulant that people need for various reasons, such as blood clots or a heart attack. But warfarin is very difficult to regulate, in part because what you eat can change the effectiveness of the drug, and there are a myriad of drug-drug interactions. The blood can get way too thin, so easy bruising can occur if the warfarin levels get too high, or the levels can get so low that it stops working and a lethal blood clot can form.

Pradaxa, particularly in patients with atrial fibrillation, will be much more reliable in maintaining the right amount of anticoagulation to prevent a stroke, and it may replace warfarin for other indications. It is usually taken orally twice daily. Because dentistry often involves surgery, therefore bleeding, there's less concern when these patients are taking this new drug compared with warfarin, and patients do not usually need to take regular blood tests to measure their degree of anticlotting. Although the data are preliminary, patients may only need to stop the drug for a day before dental surgery or perhaps not at all prior to an extraction, for example. It's a nice advance in medicine for stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation and for their dentist who needs to provide dental surgery.