Biomarkers of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) -- commonly referred to as Lou Gehrig's disease -- begin developing in teeth during childhood, according to a study published on May 21 in the Annals of Clinical and Translational Neurology.

Evidence from teeth showed that adults who develop the neurodegenerative disease broke down metals differently than people who didn't develop the disease, and this dysregulation starts during the first 10 years of their lives, according to the authors.

"Our study reveals direct evidence that altered metal uptake during specific early lifetime windows is associated with adult-onset ALS," wrote the authors, led by Claudia Figueroa-Romero, PhD, of the neurology department at the University of Michigan.

Fatal with few clues

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis affects nerve cells in the brain and spinal cord. The progressive degeneration of motor neurons causes them to die, and the brain loses its ability to initiate and control muscle movement. Many patients eventually become totally paralyzed. People often develop the disease in their 50s and 60s. Some believe ALS is linked to environmental factors, but no one has pinned down which ones.

Nevertheless, evidence has shown that deficiencies and excesses of essential elements and toxic metals are implicated in ALS. The current study, which was funded in part by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, aimed to determine at what age metal uptake dysregulation occurred in those who were diagnosed with ALS as adults.

Researchers used lasers to map growth rings in teeth from autopsies or dental extractions of 36 patients diagnosed with the disease and 31 control participants. They obtained time series data of metal uptake in the teeth.

Those who developed ALS showed increased uptake of a mixture of metals, including zinc, tin, nickel, chromium, and manganese, the researchers found.

People with ALS showed increased uptake of chromium after age 10 and had 1.49 times higher levels of this metal than those in the control group. However, manganese was significantly higher from birth through about age 6 in those with Lou Gehrig's disease. The uptake of this metal dipped significantly for these patients between the ages of 12 and 15. Their manganese levels were 1.82 times higher than in patients who didn't have ALS, the authors wrote.

Between the ages of 6 and 10, patients with ALS had increased uptake of nickel. Their nickel levels were 1.65 times those of the control participants. From birth to 2.5 years old, tin uptake increased for those who had the disease. Their tin levels were 2.46 times higher than in the controls.

Finally, those with ALS had zinc levels that were high from birth through age 15. Zinc levels were 2.46 times higher in these patients, Figueroa-Romero and colleagues found.

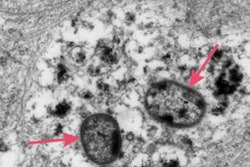

The researchers also observed metal uptake dysregulation in tooth biomarkers from an ALS mouse model, and they found differences in the distribution of metals in ALS mouse brains compared with control mice.

A few limits

The study had some limitations, including its sample size. Because ALS is a late-onset disease, and in many cases, teeth have been extensively restored or are absent at the time of death, it can be difficult to obtain preserved permanent teeth. Also, the lasers used are not ideal for measuring elements such as aluminum, fluoride, iron, and mercury. This prevented the researchers from studying their effects on the disease, the authors wrote.

Future studies that use tooth-matrix biomarkers to gain insight into alterations from racial/ethnic differences, lifetime smoking exposure, and geographical locations may lead to the discovery of a causative link.

"The current data supports the link between early life adverse systemic elemental dysregulation and adult-onset neurodegeneration," they wrote.